Frank Herbert’s DUNE is having it’s time in the sun once again thanks to Denis Villeneuve’s 2021 film adaptation, and it’s introducing a whole new crop of fans to the DUNEverse.

As an avid fan of the DUNE saga myself, I think this is great. It gives those of us who are well established in the lore and canon more people with which to enjoy DUNE-related discussions.

As many will no doubt delve deep into the lore of DUNE and consume its related content, including David Lynch’s 1984 film adaptation, the DUNE & Children of DUNE TV miniseries, and the various documentaries, they’ll no doubt come across the Jodorowsky’s DUNE; the account of Alejandro Jodorowsky‘s failed attempt at his own original film adaptation.

My Beast Monkey friends and I have been discussing this (un)fortunate turn of events (depending on which side our conflicting points of view you take). Specifically, in light of the fact that we’ve all recently subjected ourselves to viewing David Lynch’s film adaptation (and also recorded a film companion podcast episode for you all to enjoy as you watch… ) I’ve argued that Jodo‘s version would be no better, and in fact—in my own personal belief—would have been much worse than Lynch’s already questionable version.

Having watched this documentary—and various other commentaries attempting to explain the failed project—in an effort to absorb and understand his intentions, his personal journey, his struggles with the behemoth task that bringing the DUNE story to film would invariably entail, and finally the proposed storyline for his film, I wholeheartedly believe that his film adaptation would have fared no better than Lynch’s own troubled take (which is a whole other kettle of fish), and would in fact have fared much worse.

Alejandro Jodorowsky

Alejandro Jodorowsky, for the uninitiated, is a Chilean-born, French-trained mime, film-maker, artist, novelist, poet, sculptor—the list goes on. He is what you might consider a modern Renaissance man of the visual & language arts.

He’s most commonly known as an independent avant-garde film-maker whose work plays with provocative concepts in religion, mysticism, violence, surrealism, and nudity. Controversy and notoriety have earned him a nontrivial cult following as a result.

His debut film, Fando y Lis (1968), pushed the envelope of social acceptability so far that it caused a riot during its premiere, and was consequently banned in Mexico. His other films: El Topo (1970), The Holy Mountain (1973), Santa Sangre (1989), and The Dance of Reality (2013) all share his surreal signature storytelling style, and are surprisingly quite highly rated given their twisted and provocative content.

To clarify my own thoughts on Jodo, I want to first make sure that my point of view about his DUNE project should be not confused with my thoughts on the man himself, his art, or his talent.

In all honesty, despite a 50+ year difference, I feel somewhat of a kinship with Jodo both as an artist, and as a fellow countryman.

I believe him to be an incredibly creative individual who has a unique and twisted way of seeing things, and an incredible confidence in his work. His visions are grand, transcendent, provocative, wild and sometimes even terrifying.

He has a talent for not only imagining and conceiving art, but also creating it and bringing it to life. He is, in the truest sense of the word, an artist. He seeks to create and tell stories in his own singular way; that is an incontrovertible and undisputable fact.

I want to… make sure that my point of view about his DUNE project should not be confused with my thoughts on the man himself, his art, or his talent.

Having said that, although I can accept his films for what they are and can mostly grasp his intentions and meaning, I will fully admit that they’re not to my personal liking.

He mostly comes across to me as a provocateur; a troll, which by no means invalidates his work if that’s his intention, but it’s not something I truly enjoy. I see the spark of genius in his work, but his execution leaves for me a lot to be desired.

On His Work for DUNE

Whatever your own opinions on the man and his achievements, it could be argued that his greatest accomplishment was bringing people together from all over the world and uniting them to create his production of DUNE.

To bring together and secure such names as Chris Foss, Jean Giraud, H.R. Giger, Dan O’Bannon, Pink Floyd, Mick Jagger, Salvador Dali, Orson Welles, among other notable art, film &, music production talent from the 70s to attempt to secure the film under his direction was no small feat, especially if you consider that some of them had never even read the book!

He plucked them out from all corners of the world, convinced some of them to relocate to France to work on his vision, and made no small amount of deals with others to secure their involvement.

He was truly a man on a mission.

Jodo’s (and his team’s) work for his DUNE production was at the time ground-breaking, and exhaustive. Jodorowsky’s DUNE, the production Bible that depicted and described each and every element of the film; from camera angles to storyboard; costume and prop design to sci-fi concepts; technical to practical was praised for its thoroughness. It was an all-in-one tome, of which 20 copies were produced and given to all of the major studios at the time.

This tome—it’s visualisations, storyboards, designs and concepts—is renowned for having inspired and influenced scenes and designs in many of today’s greatest modern sci-fi film franchises: Star Wars, Alien, Terminator, Total Recall, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Contact, Prometheus, among many others. And as a natural progression, spawned many other ideas that resulted in some of the most renowned films in Hollywood history. It is indeed believed by many that this was a pivotal point in modern film design.

The fact that many of them went on to work on other sci-fi Hollywood greats says a lot.

Defiling of the Canon

I honestly have no doubt that Jodo’s production of DUNE would have been hailed as a grand and elaborate affair, with amazing costumes, sets, sci-fi concepts, props, visuals, and photography. My argument isn’t that his skill at conceptualising, designing, writing, producing or directing the film was lacking, it’s wholly and only that he was not interested in telling the story of DUNE as Frank Herbert had written it. He was solely concerned with his own interpretation, execution, and intent for the film.

His original account of the DUNE story differs wildly from the original, as his own storyboard drawings will attest. From it’s introductory scenes featuring dog-beings, landscapes with jellyfish composed of vegetal matter, building-sized beetles, and a depiction of a crucified Paul Muad’Dib; to its end scene where Paul is killed but is transferred to the consciousness of every human being, and the planet Arrakis itself being transformed from a desert world, to a lush green and fertile sphere, which then somehow makes its way out of the universe and into a void. The story is largely an all-out fabrication from Jodo’s mind having little to no relation to the source material.

He admittedly wasn’t trying make DUNE, he was trying to rewrite it. To tear it apart in order to rebuild it in his own vision and style. He was using it as a vehicle to further his own agenda to create a masterpiece that, in his words, “would change humanity and expand human consciousness.” A noble, but wholly unrealistic and, dare I say, wildly conceited goal.

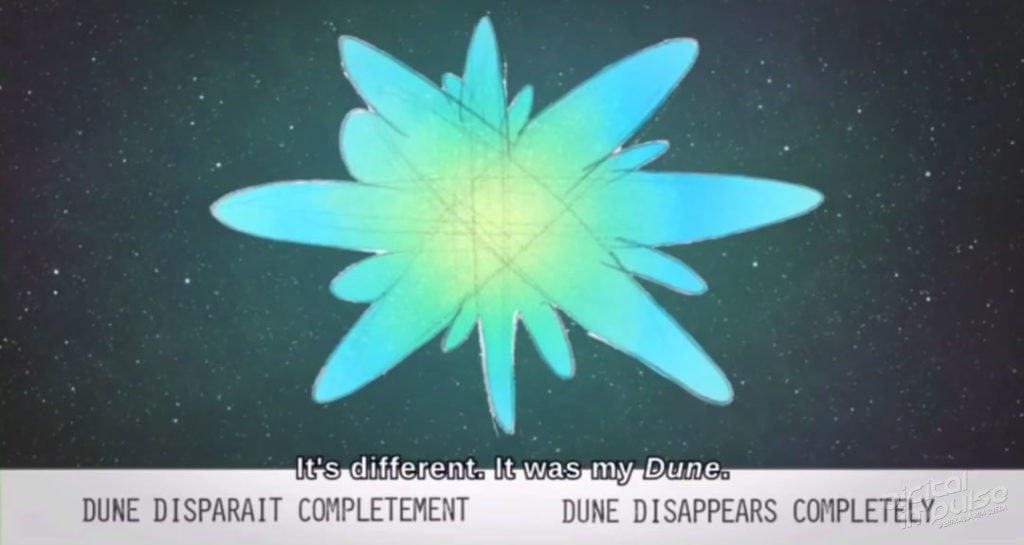

He says, of his story’s ending:

“I changed the end of the book evidently.

Alejandro Jodorowsky — Jodorowsky’s DUNE

In the book, it’s a continuation. The planet never changed.

It’s not awake with a cosmic consciousness. It’s not a Messiah; the planet.

I did that. It’s different.

It was my DUNE.”

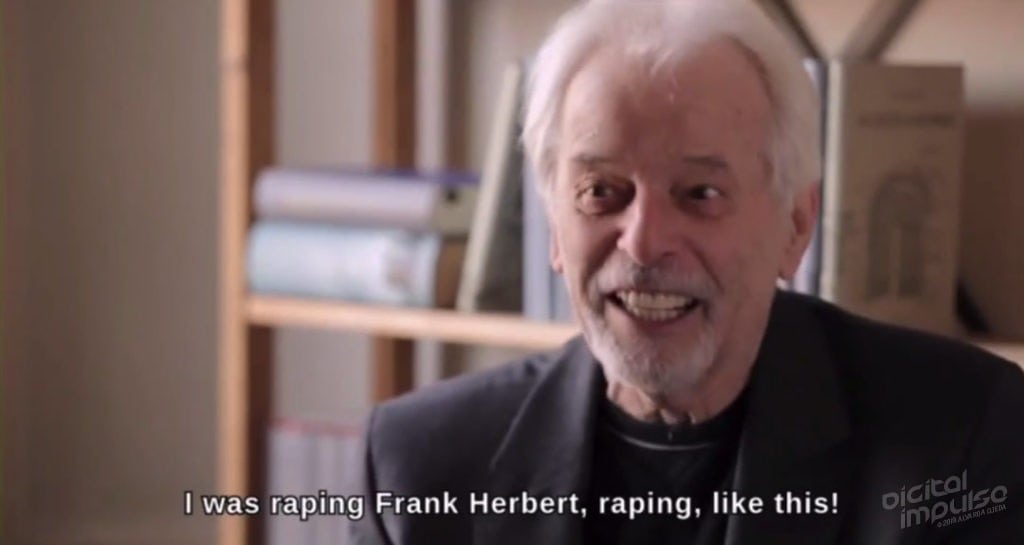

He simply did not respect the canon as it was written by Herbert. In his own words, in a statement that appears highly charged and controversial these days, and one for which Jodo himself has been criticised and rebuked, he says:

“When you make a picture, you must not respect the novel.

Alejandro Jodorowsky — Jodorowsky’s DUNE

It’s like you get married, no? You go with the wife, white, the woman is white…

You take the woman. if you respect the woman, you will never have child.

You need to open the costume and to… to rape the bride.

And then you will have your picture.

I was raping Frank Herbert, raping, like this!

But with love… with love.”

This, above all, is the crux of my argument. He was more concerned with how to bend and distort the story in order to tell his own account of the narrative for his own purposes.

I understand that film-makers will invariably change and adjust literary works to suit their own ends; to fit the story within a given amount of time; or to satisfy a specific premeditated narrative or agenda; to appease executives’, producers’, or an audiences’ perceived needs; or to simply take artistic licence and add their own unique flavour to the piece. As an artist, I get that.

I’m not saying his work wasn’t revolutionary or transcendent. I’m also not saying he wouldn’t have told a great story, or that the concepts, visuals, music & design could not have been ground-breaking.

My point, honestly and wholeheartedly, is that I don’t think such a great work of literature as DUNE needed to be sacrificed solely to accomplish his goals—DUNE need not be sundered on the altar of Jodorowsky.

DUNE need not be sundered on the altar of Jodorowsky.

I ultimately think Frank Herbert’s DUNE as a story in and of itself can and should stand on its own. Herbert created a masterpiece, full of life, mystery, and insight. Dealing with philosophy, religion, ecology, biology, physics, metaphysics, and more; it is a rich and wonderful tapestry of text that aims to get at the very heart of humanity itself. It deserves to stand on its own for what it is, and to be respected as such.

A Lipsticked Slig

But in the case of Jodorowsky’s DUNE, I think the man’s ego at the time overshadowed this story. I’ve no doubt that had his version been made it would have added to his cult following, and earned its own—much like Lynch’s version, but it would simply not have been DUNE.

I also believe his vision for the film was simply too far ahead of its time, technically, conceptually, and practically. And had he been allowed to go ahead with it I think it would’ve flopped as spectacularly as the Lynch version did, if not more so.

It may indeed have been lauded as the most fantastic, visually stunning, and imaginative film ever made, but given the state of film design (special effects, costume & set design, make-up, etc.) at the time, I believe it would have suffered, and would not have aged well at all.

Looking at the production critically, given the stated actors, the designs, storyboards, and direction—having reached completion—I imagine it would’ve resulted in something the likes of 1960-70’s Star Trek, mixed with 1980’s Flash Gordon, with a large degree of camp, pretentiousness, violence, gore, nudity and adult themes; the standard Jodorowsky recipe, to be sure.

Perhaps it might even resemble something like the ’90s Lexx, which is a production that could rightly fit into the So Bad It’s Good category; loveable for its proud and unabashed cheesiness and camp, but also intermixed with veins of dark themes, deep philosophy, religion, sexuality and morality. It is an experience all its own but one with an undeniably niche audience.

But really, can you imagine the production hell Jodo’s film would’ve been!? Between Jodo, Dali, and Welles alone you have a recipe for disaster. But throw in your film executives & producers, and you’d have had egos clashing, budgets exceeded, and set drama like you would not believe. It would’ve been spectacular!! And I suspect would likely have crashed and burned before it saw the light of day regardless.

I baulk at the assertion that it is the most spectacular film never made, but I have to admit that in those ways it probably is. If only because it would have been a spectacular shit-show.

My Conclusion

I posit that Jodo was indeed never meant to make DUNE, and destined instead—and better served—by creating his own sci-fi creation & universe—which he did with Jean Giraud (Mœbius) in The Incal, and The Metabarons and its wonderful and twisted universe.

His vision could only be fulfilled through a creation of his own making where he could play and mould concepts to his own desire. It may not have been the medium he would have hoped for, but one nevertheless that allowed him the freedom to imagine and bring to life a universe he could wholly control without twisting a beloved and established classic into some surreal creature.

And one could ultimately see these stories themselves being adapted to film by some young intrepid film-maker to become blockbuster films or lauded television series in their own right. Netflix? Hulu? HBO? If they’re interested in creating great stories, these are some of the most imaginative.

As a series, if handled correctly, they could stand alongside such greats (and some of my most favourites) as Battlestar Galactica, Star Trek, The Expanse, Babylon 5, Farscape, Altered Carbon, and others. One can only hope.

Some things are sacred—should remain sacred. I think of Frank Herbert’s DUNE as one such thing. I also think some people may think of of Jodo’s work as such; it’s certainly original, bold, provocative, and out of the norm. But to intermingle them? To come up with some mutant combination of the two…? No, thank you.

You would have to be an absolute genius to be able to pull that off with any amount of success and despite all his talent and vision, I’m just not fully convinced Jodo had the wherewithal to pull it off to the level of a successful blockbuster film in the 70-80’s.

It’s wonderful to think that perhaps he might’ve completely changed the state of the film industry and movies themselves, but considering what we know the of the history of film and the societal mores and taboos of the time, I can only think that his attempt would’ve been panned and he would’ve been quickly dismissed and forgotten.

Some things are sacred—should remain sacred.

I think of Frank Herbert’s DUNE as one such thing.

That is a worse fate, and as bad as he may have felt things turned out, I don’t think he would’ve handled having completed his magnus opus and having it fail so spectacularly very well at all. I’m also positive that that the majority of DUNE fans would not have let it slide.

There is, however, something to be said about the general opinion of this debacle being one of positivity and missed potential on Jodo’s part. It points to the man’s talent and imagination and may help future generations to remember him fondly.

Afterword

As a final word I should mention that the time of this writing I have yet to see Denis Villeneuve’s ᑐᑌᑎᑢ production. It doesn’t screen in cinemas here until December! However, I understand that he is an avid fan of Herbert and the DUNE story in particular, so I hope his interpretation does the book justice. He did do a great job with Blade Runner, after all.

I understand he has taken his own creative license and changed some character & plot lines to suit the medium of film and his own storytelling needs, but for the most part it has been quoted that his interpretation remains quite faithful to the original source material.

The photography I’m sure will no doubt be amazing as Denis has a beautiful cinematic eye. But having seen the teasers and trailers, I will say that I find the overall look of the film to be very clean and neat. Perhaps too much so.

For a story being set on a desert planet populated by sand dwellers, there appears to be a dearth of dust & sand on the costumes and equipment; everything just appears to be pretty much well-kept, clean and dust free.

The colour grading also appears very moody and dark at times, and Denis appears to have gone with the popular washed out teal/orange mix. The overall look of the film very much fits the modern-day sci-fi genre… I’m not sure if that’s a good thing.

There also appears to be a lot of sci-fi electronic technology gadgets and doohickies. It all looks great and appears to fit the overall theme, but for my part, I find it a little disappointing that the more organic/biological design aesthetic the books describe appear to have been overlooked or altogether ignored

Ornithopters, glowglobes, crysknives and an array of other devices and objects are described as being or having elements of biological origins, selected or even necessitated by the cultural taboo of electronic Thinking Machines of DUNE lore. This was one of the aspects I most enjoyed about the Lynch version; H.R. Giger was simply the perfect artist for this aesthetic.

I’m nevertheless looking forward to watching the film and poring over its design and styling choices. So far, I hear good things.

Thanks for taking the time to read this. Feel free to post your thoughts in the comments below.

Recent Comments